How DNS works?

Before we dive into DNS I would like to start with some background to what generated the Internet as we know it today.

Definitely the creation of the DNS is one of the most important creations, specially because without it you wouldn’t be reading this now, you will understand why later on, keep reading.

In the late 1960s, the U.S. Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), began funding an experimental computer network, that connected research organisations in the United States, they called it the ARPAnet. Their goal was to allow to government contractors to share computing resources, however, users also used the network for collaboration, from sharing files and software to exchanging e-mails, to joint development and research using shared remote computers.

Later, in early 1980s the TCP/IP suite is developed, and quickly becomes the standard host-networking protocol on the ARPAnet. The inclusion of such protocol in the University of California at Berkeley’s popular BSD UNIX was instrumental in democratizing internet working. And since BSD Unix was free to universities, this meant that internetworking - and ARPAnet connectivity - were suddenly available cheaply to many more organisations than were previously attached to the ARPAnet.

Many of the computers being connected to the ARPAnet were being connected to local networks (LANs), and very shortly the other computers on the LANs were communicating via ARPAnet as well, and so the network grew from a handful of hosts to tens of thousands of hosts the original ARPAnet became the backbone of a confederation of local and regional networks based on TCP/IP, called the Internet.

Although, in 1970s ARPAnet was a small community of a few hundreds of hosts, manageable from a single file, HOSTS.TXT, containing a name-to-address mapping for every host connected to the network. Maintained by SRI’s Network Information Center (NIC) and distributed from a single host, SRI-NIC. The administrators used to email their changes to the NIC, and periodically get the HOSTS.TXT file from SRI-NIC. Meanwhile the file was updated once or twice a week, but as the network grew, this scheme became unworkable, the size of the file grew in proportion to the growth in the number of ARPAnet hosts.

When ARPAnet moved to TCP/IP, the population of the network exploded, and HOSTS.TXT was no longer a viable solution. The problem was that the single file mechanism didn’t scale well, and 3 main problems could be identified:

- Traffic and Load

- The toll on SRI-NIC, in terms of network traffic and processor load involved in distributing the file was becoming unbearable.

- Name Collisions

- No 2 hosts in HOSTS.TXT could have the same name.

- NIC could assign addresses and guarantee uniqueness, but had no control over hostnames. There was nothing to prevent someone from adding a host with a conflicting name and breaking the whole scheme.

- Consistency

- Keeping consistency of the file across the network became harder and harder. By the time the file had reached the whole network, a host could have changed addresses or a new host may have emerged.

And so an investigation was started to develop a successor for HOSTS.TXT. Their goal was to create a system that solved the problems inherent in a unified host-table system.

The new system would allow local administration of data and make that data available globally. The decentralisation of administration would eliminate the single-host bottleneck and relieve the traffic problem and local management would make the task of keeping data up-to-date much easier. Finally, it should use a hierarchical namespace to name hosts, this ensures the uniqueness of names.

That’s when Paul Mockapetris, was responsible for designing the architecture of the new system and in 1984, he releases RFC 882 and RFC 883, that describes the Domain Name System. Later those RFCs were replaced by RFC 1034 and RFC 1035, which are the current specification of the DNS and they have been augmented by many others that describe DNS security problems, implementation problems, and so on…

DNS, in a Nutshell

The DNS is a distributed database. This structure allows a local control of the segments of the overall database. The data in each segment is available across the entire network through a client/server scheme. The way this system achieves robustness and adequate performance are achieved through replication and caching.

A program called NameServer is the server side of the client/server mechanism. They contain segments of the database and make the information available to clients, called Resolvers. Resolvers create queries and send them across a network to a nameserver.

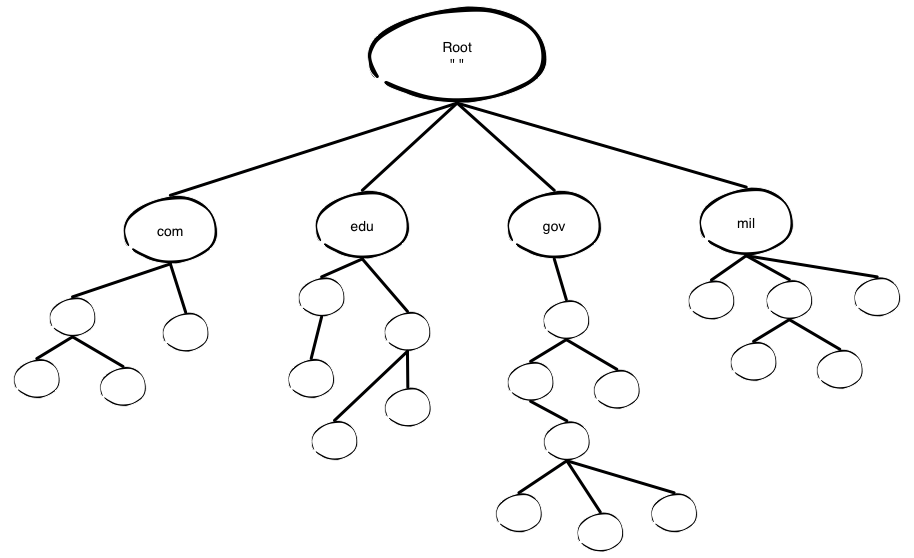

The structure of the DNS database is constituted by nodes (computers) with the “root” node on top of the tree. Each node has a text label, that identifies the node relative to its parent. Although, one label - the null label, or “ “ - is reserved for the root node. Each node is also the root of a new subtree of the overall tree, and each subtree represents a partition of the overall database. Each domain can be further divided into additional partitions called subdomains. Every domain has a unique name and also identifies its position in the database.

Nowadays there are 13 root servers, every single one of them starts with a letter, from A to M, and we can see them when you use the command line tool dig, which is a flexible tool for interrogating DNS name servers. It performs DNS lookups and displays the answers that are returned from the name server(s) that were queried.

~ $ dig +trace davidslv.com

; <<>> DiG 9.9.5-3ubuntu0.5-Ubuntu <<>> +trace davidslv.com

;; global options: +cmd

. 518400 IN NS E.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS F.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS G.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS H.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS I.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS J.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS K.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS L.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS M.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS A.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS B.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS C.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.

. 518400 IN NS D.ROOT-SERVERS.NET.You can see in that trace that it starts by going through the root servers before going through the global tld (top level domain) servers and then goes through the name-servers and finally gets the IP addresses of the hosts associated to the domain name.

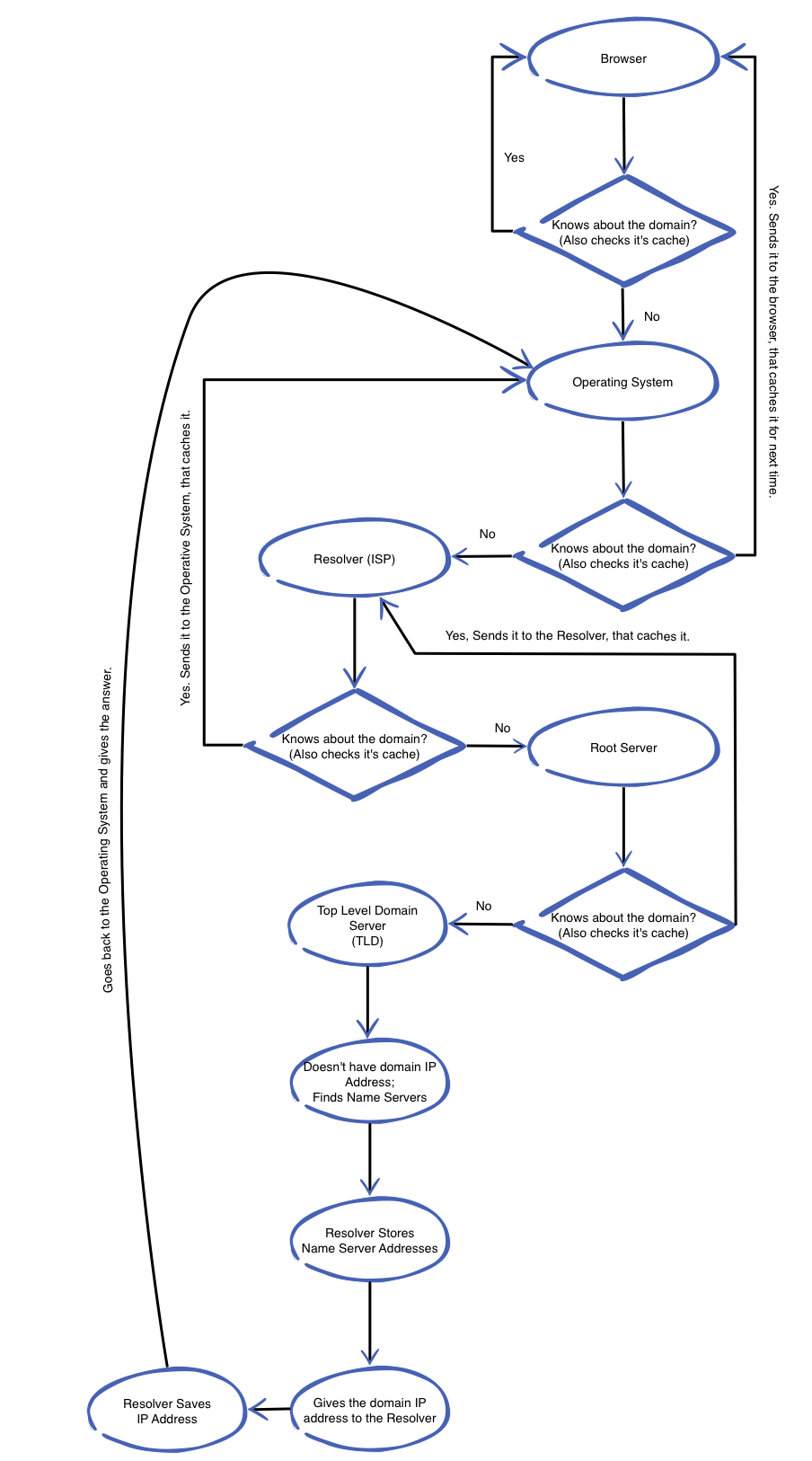

I would like to show you a diagram, that represents my own interpretation of how the DNS works, I don’t intend it to be more complex than needed, so don’t rely entirely on it because it might be missing a lot of things, remember that the DNS is a complex system, there’s many things involved, and in order for us to receive information in seconds there’s is a bunch of things that happen in the background. I think it’s fascinating!

I would like to complement this article with some references:

Piskvor, http://stackoverflow.com/a/2092602/204752

Pete Keen, https://www.petekeen.net/dns-the-good-parts

DNSimple, amazing story https://howdns.works

Cricket Liu, Paul Albitz. 2006. DNS and BIND, 5th Edition, O’Reilly Media

Thank you for reading,

David Silva